WHAT’s gold got to do with the UK trade deficit?

Bullion.Directory precious metals analysis 12 May, 2016

Bullion.Directory precious metals analysis 12 May, 2016

By Adrian Ash

Head of Research at Bullion Vault

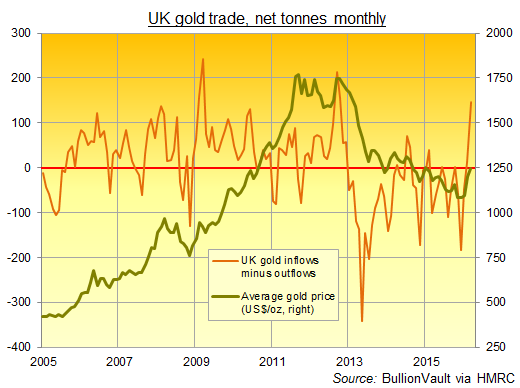

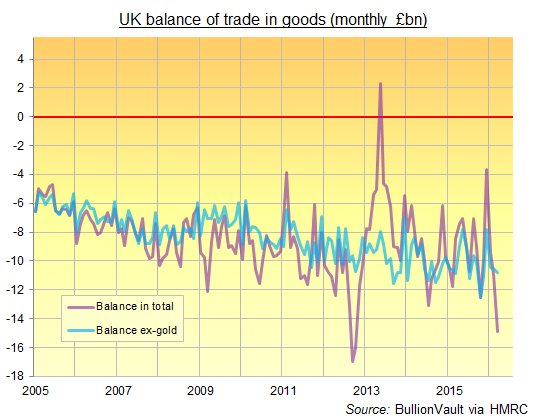

Yet the biggest quarterly gap between UK imports and exports since 2008 just came thanks to the heaviest net inflow of gold bullion since autumn 2012…accounting for £3.4 billion out of the total trade deficit of £13.3bn reported for January and March 2016 on the Office for National Statistics’ data.

Anyone could have seen this coming, in truth. Because gold prices rose in Q1 at their fastest quarterly pace in almost 30 years…

…and when gold prices go up, gold tends to flow into London. Because it is the central vaulting and dealing point for wholesale gold bullion worldwide.

Despite having pretty much zero mining, manufacturing or gold demand, the UK has in fact been the world’s fourth largest gold importer and the second largest exporter over the last 5 years.

So this week’s sudden hoo-ha over the UK’s trade deficit misses the huge swing in gold flows. After flattering the headline balance since 2013 by showing a net export, gold added £4bn to March’s net imports bill alone, thanks to that sharp upturn in gold prices on a surge in large allocations in London, plus a drop in Asian demand.

“Gold held in allocated accounts is recorded as a good,” said HMRC when it updated and changed its reporting in 2014, “in contrast to monetary gold, which is a financial asset,” as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) put it when first changing its guidance – which the UK took 7 years to catch up with – in 2007.

The data shown above, in other words, don’t count any central-bank reserves (of which the Bank of England is the largest custodian outside the New York Fed, holding more bullion than Fort Knox). What they do count is “gold…being stored as a financial asset…recognised under trade in goods when ownership changes between a resident and non-resident.”

Not all the Q1 inflows, therefore, were necessarily shipped into the UK between January and March. Some bullion very likely sat in London’s specialist vaults already, but ownership changed – from a foreign owner to a UK resident – as prices rose (or vice versa, if you prefer).

So we could, and might well, return in time to see quite how the ONS crunches these numbers, “working [as it says it does] alongside the Bank of England and the London Bullion Market Association [to] implement…a method for smoothing the source data; effectively minimising volatility whilst enabling the underlying trend of the gold market to be reflected in the trade balance.”

But for now – and noting that gold bullion counts very much in the “erratic” category of the ONS number-crunching, as it reminds everyone in its first release each month – two things:

First, the UK’s trade data now appear gross of gold inflows and outflows. Some months, that will have a significant impact. It took the UK’s tax authorities and national statistics agency until 2014 to add “non-monetary gold” to their import and export data after the IMF made its position clear in 2007. That, together with the apparent “smoothing” and caveats stated by the ONS, suggests a degree of resistance, no doubt because London’s centrality to world gold flows meant they were always likely to impact the UK’s headline trade balance figure dramatically.

Second, and contrary to what else you might stumble across on the internet today, London’s vaults are a long way from empty. Net UK gold inflows over the last 11 years total 1,500 tonnes – around half a year of global mine supply – on the reported data. Who knows what was stockpiled before that data series begins in 2005.

And if you won’t believe the data’s blunt headline, believe instead the plentiful supply any would-be buyer will find when calling for a price from London’s bullion banks, dealers and brokers right now.

There is no shortage. That came, after a fashion, and soon went again, only after prices sank in 2013. But not here in 2016. Because prices have been rising.

Bullion.Directory or anyone involved with Bullion.Directory will not accept any liability for loss or damage as a result of reliance on the information including data, quotes, charts and buy/sell signals contained within this website. Please be fully informed regarding the risks and costs associated with trading in precious metals. Bullion.Directory advises you to always consult with a qualified and registered specialist advisor before investing in precious metals.

Material provided on the Bullion.Directory website is strictly for informational purposes only. The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information. No information on this website is intended as investment, tax or legal advice and must not be relied upon as such. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. Precious metals carry risk and investors requiring advice should always consult a properly qualified advisor. Bullion.Directory, it's staff or affiliates do not accept any liability for loss, damages, or loss of profit resulting from readers investment decisions.

Material provided on the Bullion.Directory website is strictly for informational purposes only. The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information. No information on this website is intended as investment, tax or legal advice and must not be relied upon as such. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. Precious metals carry risk and investors requiring advice should always consult a properly qualified advisor. Bullion.Directory, it's staff or affiliates do not accept any liability for loss, damages, or loss of profit resulting from readers investment decisions.

Leave a Reply