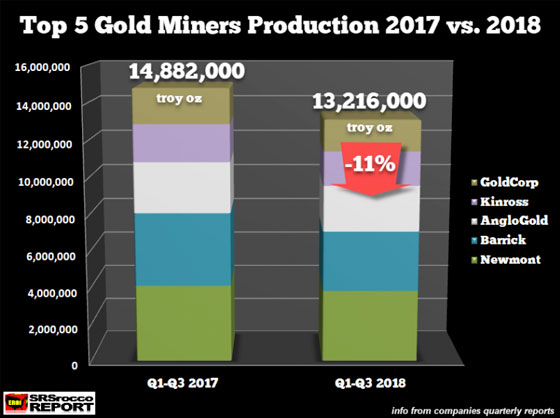

During the lackluster and otherwise unremarkable trading of 2018, a hugely important development took place in the precious metals markets. Gold production, in the estimation of some top industry insiders, peaked.

Bullion.Directory precious metals analysis 01 February, 2019

Bullion.Directory precious metals analysis 01 February, 2019

By Stefan Gleason

President of Money Metals Exchange

Peak gold represents the point at which the total number of ounces being pulled out of the ground by miners reaches a maximum.

It doesn’t necessarily mean gold production will suffer a precipitous fall. But it does mean the mining industry lacks the capacity to ramp up production in order to meet rising global demand and even higher prices would not make it happen.

One of the leading proponents of the peak gold thesis is Ian Telfer, chairman of Goldcorp (which was recently acquired by Newmont Mining to become the world’s biggest gold company).

Telfer remarked in 2018, “In my life, gold produced from mines has gone up pretty steadily for 40 years. Well, either this year it starts to go down, or next year it starts to go down, or it’s already going down… We’re right at peak gold here.”

We’ll soon find out whether his call for gold production to fall in 2019 pans out. If it does, the implications for precious metals investors are enormous.

The concept of peak gold is controversial, to be sure.

Skeptics point to the thwarting of peak oil over the past decade. Just as technological breakthroughs in fracking and horizontal drilling caused an unexpected surge in crude oil supplies, could not advances in gold mining techniques also lead to an unforeseen supply surge?

When human ingenuity combines with the right market incentives, nothing can be ruled out. But unlike crude oil which is a byproduct of decayed living organisms and exists in various grades all over the world, gold is a basic element that came to us from exploding stars billions of years ago.

The amount of gold in earth’s crust is fixed. By contrast, oil and other hydrocarbons can be produced synthetically from renewable biomass.

Perhaps one day we’ll mine for gold in space or generate it in nuclear reactors or particle accelerators. Theoretically, it’s possible. Practically, there’s no prospect of these unconventional methods of boosting earth’s gold reserves becoming economically viable in our lifetimes. It would take a true “moon shot” in the gold price and/or a technological breakthrough that might be decades away from coming to fruition.

In the meantime, the gold mining industry is experiencing a major wave of consolidation.

Last year Barrick Gold and Randgold merged. This year Newmont Mining acquired Goldcorp. Many lesser known junior mining and exploration companies have been or may soon be gobbled up by senior producers looking for an economical way to grow their reserves.

Developing new mines is expensive, time consuming, and risky.

It’s difficult these days for the majors to even identify viable new projects that would add significantly to their asset base. As new discoveries shrink, many have decided it makes more sense to buy up the assets of smaller competitors while they are on sale.

It may prove beneficial to corporate bottom lines, but M&A activity doesn’t necessarily translate into more ounces being pulled out of the ground on an industry-wide basis. To the contrary, it’s a sign that mining companies aren’t keen on investing in the exploration and development of new mines.

After years of “high grading” – processing the easier to get, higher quality deposits first – future gold extraction costs could get progressively steeper for existing major mines.

Even at $1,300 an ounce, gold prices aren’t high enough to generate attractive returns on investment. Many gold mining companies are barely breaking even after their all-in costs are considered.

Canadian mid-tier producer Iamgold announced recently that it will halt construction at one of its gold projects in Ontario. Iamgold CEO Stephen J.J. Letwin said the company will “wait for improved, and sustainable, market conditions in order to proceed with construction.”

That’s just one example among many of why gold production could begin to taper off and decline overall in 2019.

Refinitiv GFMS analysts forecast gold mining output will decrease slightly this year – from approximately 3,282 tonnes in 2018 to 3,266 tonnes.

The expected fall-off may not be huge, but the wider impact on the precious metals markets very likely will be. With central bank buying continuing to be robust, jewelry demand in India back on the upswing, and investor interest returning amidst volatile financial markets, a slight decrease in production relative to rising demand — sets the stage for a rip-roaring secular bull market.

Material provided on the Bullion.Directory website is strictly for informational purposes only. The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information. No information on this website is intended as investment, tax or legal advice and must not be relied upon as such. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. Precious metals carry risk and investors requiring advice should always consult a properly qualified advisor. Bullion.Directory, it's staff or affiliates do not accept any liability for loss, damages, or loss of profit resulting from readers investment decisions.

Material provided on the Bullion.Directory website is strictly for informational purposes only. The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information. No information on this website is intended as investment, tax or legal advice and must not be relied upon as such. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. Precious metals carry risk and investors requiring advice should always consult a properly qualified advisor. Bullion.Directory, it's staff or affiliates do not accept any liability for loss, damages, or loss of profit resulting from readers investment decisions.

Leave a Reply